The witches’ dance

… there is no assembly carried on where they do not dance.

– Jean Bodin, On the demon-mania of witches (1580)

My interest in the works of the early modern demonologists, and their descriptions of the sabbat, began with the afterlife of the witch or sorceress in the early modern dance of the twentieth century. The witch survives, perhaps most strikingly, in Mary Wigman’s Hexentanz, a choreography which transformed over three incarnations, each created under a different political regime [1]. A dance innovator and feminist, Wigman engaged with the early to mid twentieth century German scholarship on the witch hunts, which spanned the irrationalist romanticism of thinkers such as Grimm and Nietzsche to the mystical neopagan and völkisch movements. Across shifting ideologies and cultural influences, the witch in Hexentanz I and II embodied a rejection of modernity and industrialisation, liberating the body – specifically the female body – in a movement that aligned political with aesthetic freedoms.

Wigman, Hexentanz II (performed 1926, filmed 1930)

The witches’ dance was a catalyst for my own work, as I sought to devise a personal dance from the genealogy of butô which I’d received from my teachers. As the central image in the formula of the sabbat, the sinistrous circling dance draws together the peculiar themes and motifs associated with witchcraft: shapeshifting, spirit congress, flight, forbidden sexuality, poison, violence, dream, horror. Its movement is palintropic, always returning to its beginning, and thus evokes the powers of arche and archaios: of command, of bringing forth, of the dead, and of the archaic. And binding it all in a weyward dance, daemonic communion with all, a common flesh.

It matters not that the sabbat is an artful and late construct, as I found there a glyph for what had been hidden or silenced, or never permitted to come forth; just as the harlot of Revelation glyphs the forbidden totality of woman: bodies, histories, voices singularly expressive of a defiled feminine divine. I understand my dance practice as an archaeology of the flesh, which brings to light what is buried in our body consciousness and liberates our potential. I conceive of my body and its interior landscape as a terrain sorcier through which I engage and explore the occulted dimensions of place and the ecology of spirit. The sabbatic dances were incorporated within a wider practice of presence, observance, walking, moving, and ritual actions in the land.

In this essay I trace the haunted kinaesthetic and psychic territories of witchcraft through a history of disorderly movement and unruly bodies, and situate the dance in its sociopolitical context. The origins of the witches’ dance are to be found primarily in the narratives constructed by the demonologists from the late medieval to the early modern periods, and in the testimony of accused witches, but can also be sought in a range of other materials – textual, oral, iconographic, ethnographic and archaeological. Dance is a kinetic and kinaesthetic tradition, it is communicated most effectively from one body to another; but the witches’ dance, a demonological fantasy, has been transmitted primarily through texts, and it is to these other bodies I will initially turn to retrieve the dance.

Early references to a witches’ assembly or sabbat, such as we find in the Canon Episcopi (c.900 ce), do not mention the dance. Kramer and Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum, published in 1486, omits the sabbat, and mentions only the dancing of satyrs, understood as demons [2]. The dance first came to prominance as a feature of the witches’ sabbat in Rémy’s Dæmonolatreiæ libri tres (1595), associated with the pagan rites of antiquity, moving contrariwise and governed by the law of inversion; an account that became the paradigm for later elaborations. Although, in the earlier texts when the dancing conspiracy has not yet been formulated, we see the congregation of bodies and themes which will coalesce into the witches’ dance of the later demonologists. Bernardino of Siena, in a sermon against witchcraft from 1427, describes a nocturnal assembly of witches witnessed by a page in the service of the Vatican.

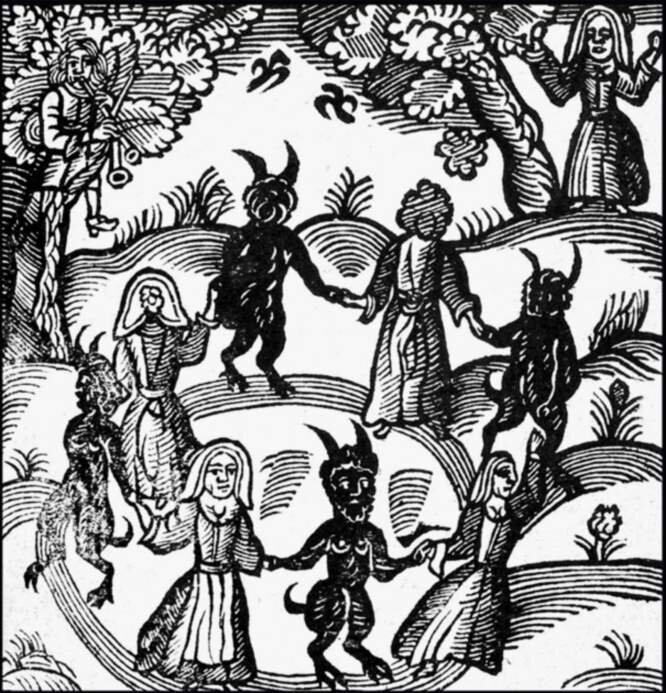

Witches and demons creating a circle.

Nathaniel Crouch, The Kingdom of Darkness, 1688.

Journeying by night to Benevento, a place already infamous for witchcraft, he came across a gathering of people dancing on a threshing floor. At first fearful, he nonetheless joins the revelry which ends at dawn with the ringing of the matin bell and the sudden disappearance of those gathered. In his article on Bernardino’s sermon, Michael Bailey [3] proposes that interrogating the story – and specifically those aspects relating to the nocturnal revels – may bring light to certain elements that were incorporated into evolving ideas of a diabolic, conspiratorial witchcraft [4]. He suggests, for instance, that the location of the dance on the threshing floor might indicate that Bernardino knew of nocturnal rites and ritual dances linked to agricultural fertility; and thus that such practices, and the popular beliefs they expressed, were integral to the formation of early modern notions of witchcraft.

The place of the dance is a notable detail; the threshing floor was not a feature of later sabbat narratives at Benevento, which were focussed on the walnut tree. The threshing floor is an essentially agrarian structure, and in early societies would certainly have been the largest communal space; circular in form, they were ‘places of gathering, encounter, witness, and transformation, […] across the ancient Mediterranean.’ [5] The coming together of a community around the life-sustaining activites of threshing and winnowing made the threshing floor an important nexus of village life. They were places of sacred significance, associated with the dead, and a focus of the village’s cultic life and celebrations. Gathering together at the threshing floor creates a sense of communitas, a circle of equals or insiders quite unlike the diabolic circle of witchcraft imagined by demonologists.

Threshing floor, Naxox. Photograph by Margaret M. Miles

As the stereotypical features of the witches’ sabbat emerged, with the transformation of folk beliefs as they were incorporated into and interpreted within the elite theological discourse, the witches’ dance was frequently situated at the heart of a sabbatic inversion of order. The sabbat was sometimes simply called ‘the dance’ and, as Willem de Blécourt recounts, inquisitors would interrogate the accused ‘about the length, frequency, and place; whether they ate or drank first, what they ate, how it tasted, how they danced, with whom, in what order.’ [6]

Lyndal Roper notes the disparity between the grotesque depictions of the sabbat by the demonologists, or artists such as Salvator Rosa, and the more mundane testimony of the alleged witches. She observes that, ‘they have all the character of a church ale, the local festivals of eating, drinking and dancing organized by peasants.’ The place of the dance in the testimonies – under the lime trees, on the moor, by the witches’ hedge, the square in front of the church, the market place, by the gallows – suggests that ‘these village and small-town witches […] grounded their fantasies in the experience of the local dance.’

The dance, which identifies participants as belonging to the diabolic sect, is arguably the least fantastical element in the sabbat complex. As Roper notes, it is physically based in the places and experiences of those involved. Dance was ever-present in people’s lives from the late medieval period to the middle of the eighteenth century, the period when the various demonological constructs of the sabbat circulated in the European imagination. [7]

But it is also important to recognise what Susanne Langer saw as the virtuality of dance. Langer’s ‘virtuality’ conveys how intense experiences are more real than the activities or objects that give rise to them. [8] In dance, force manifesting as movement and gestures traced by bodies in the world give rise to an affective, inner experience or perception which is more than real, going beyond the physical or material aspects of movement to return to the immaterial or imaginal dimension. In butô a similar process is expressed by the concept of nikutai, the carnal body that manifests the interior landscape, the body that is moved by internal or imaginal environments as well as external forces. Movement inscribes and articulates both physical and psychic spaces, and there is continuous exchange between material and immaterial, and between outer and inner perceptions. In dance the surreal and the supernatural form a continuum with the real and the mundane; this is markedly true of the witches’ dance, and of the witch herself.

Of particular note is the supernatural element in Bernardino’s sermon: at dawn all the dancers disappear except the girl with whom the page had danced and held onto at the ringing of matins. Throughout Europe nocturnal fertility rites and revels were associated with supernatural figures such as Oriente, Abundia, Holda, Diana, Herodias and Perchta who led night-journeying processions of benevolent spirits. Ronald Hutton accepts that these processions ‘may well have pre-Christian origins, and probably contributed directly to the formulation of the concept of the witches’ sabbath.’ [9] In these nocturnal rites supernatural elements are confounded with folk traditions and notions of witchcraft and sorcery. For instance, in the saying ‘Quelli che vanno a balo o, come si dire, in striozzo’ (Those who go to the dance, or as it is said, to the sabbat) the word striozzo, from stria (witch), refers not only to the witches’ nefarious activities, but in popular idiom also denoted the licentious dancing feasts that followed the harvest. [10] Yet the popular perception of these feasts was not diabolic; allegiance to the Devil was not implied by the bawdy humour and wanton dancing. The spiritual creatures most closely associated with dancing in popular consciousness were not demons, but fairies.

In The Anatomy of Melancholy Robert Burton describes fairies as ‘these are they that dance on heaths and greens.’ [11] In his study on the fairylore of Elizabethan England, Minor White Latham described them as being ‘inordinately addicted to dancing. With them,’ he writes, ‘it amounted almost to a natural means of locomotion, especially in England,’ [12] and the countryside bore the marks of their dancing circles.

It has been noted that fairylore often functions as a repository of customs that have become socially and culturally obsolete. The fondness of fairies for dancing may thus be a folk memory of the ring dances that were once popular. Fairy rings, circular traces believed to have been made by fairy dances which leave the grass parched or spotted with mushrooms, were also attributed to witches. The night dancing of witches and hidden folk alike is a superstition found throughout Europe, for instance the French ronds de sorcières, and the German Hexenringe, with a wealth of lore associated with them.

Robin Goodfellow, his mad prankes and merry jests (1628)

There are a profusion of shared motifs in accounts of the fairy folk and of witches. Beliefs about them frequently overlapped, as has been noted by Lizanne Henderson and Edward J. Cowan in Scottish Fairy Belief. [13] This conflation of familiar folklore elements with a politically and theologically inspired diabolism is what we see in Dæmonologie, wherein King James states that, ‘Witches have been transported with the pharie to a hill, which opening they went in and there saw a fairie queen who […] gave them a stone that had sundrie vertues.’

The intercourse between these realms is thereby established and the fairies shown to be nothing but airy illusions of the Devil. Yet, if the demonic masked traditional lore, it did not erase it; in the transference of fairy motifs to witches, that lore persisted.

Olaus Magnus, On Nocturnal Dance of Fairies, in Other Words Ghosts

Fairylore itself could provide sanctuary for practices and pastimes that were no longer current among the people. In her article on the prohibition of dance in Iceland, Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir examines ‘how repressed culture can find expression in legends,’ specifically how oral traditions about the hidden people preserve memories of dancing after its suppression by the Church. [14] Ecclesiastical disapproval of nocturnal dancing parties, and the excessively hedonic drinking and love-making that went with them, led to ‘deliberate efforts … to eradicate parties, and thus, dancing from Icelandic culture.’ As a result of these efforts, dance amongst the people died out in the eighteenth century. However, Guðmundsdóttir speculates that dancing continued with the elves, that is, in the imaginal underground or subconscious of the Icelandic people. She writes:

‘Memories of earlier dancing parties had found their way into traditional oral legends in which they became an attribute of the elves. In time, these legends, which can be seen as mirroring the national subconscious, became the last refuge of the dance and the place where the memories were kept alive.’

If fairylore preserves memories of older cultures, the ring dances or choral-ring dances may be traced back to the dancing culture of early agricultural communities analysed by Yosef Garfinkel in his ground-breaking Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture. Identifying the circle as a significant form of spatial organisation of dance in the community, [15] (and the one most suited to depiction on rounded pottery vessels), he notes that its closed structure promotes a ‘unified mood and action,’ congruent with magical and social activities. Trance and ecstasy are altered modes of consciousness that can be physiologically induced, both individually and, through an implicit sensorimotor empathy, collectively. [16] The inward focus and the rhythmic patterns of movement of the circle dance, often in combination with drugs or periods of fasting, bring about transformations in consciousness. The circle dance is a ritual form that creates a profound psychobiological synchrony between participants, and foments a heightened awareness or extrasensory perception in which all are open to experience the supermundane, and in which the integration and healing of the group and its members can take place.

Garfinkel traces the appearance of dance motifs in the Neolithic to the Near East, and their diffusion into Europe in connection ‘with rituals connected with the agricultural cycle of seeding and harvesting.’ [17] But the essentially egalitarian form of the circle, in which all dancers move equally and on equal terms in relation to the centre and each other, indicates an even earlier origin, predating the increasing social differentiation that came with the agrarian revolution. In his World History of the Dance, Curt Sachs proposed that the circle is the most archaic dance form, the origins of which go back to prehistory, thence we may ‘assume that the circle dance was already a permanent possession of the Paleolithic culture.’ [18]

‘The dance is a circle whose centre is the devil, and in it all turn to the left, because all are heading towards everlasting death. When foot is pressed to foot or the hand of woman is touched by the hand of a man, there the fire of the devil is kindled,’ wrote Jacques de Vitry (died 1240) in his Sermones vulgares, denouncing the carole. [19] The carole was the principal social dance in France and England in the Middle Ages, a dance in which all social classes participated, men and women alternately arranged in a circle and stepping to the left. The description would apply just as aptly to the witches’ dance at the sabbat as the early modern came to imagine it. The circle of dancers, joined together by holding hands, could form around an object such as a tree or could encircle an honoured person during the dance; a formation that can be recognised in descriptions of the witches turning sinister around the walnut tree at Benevento, or around the figure of the devil or one of his bestial hypostases. The only difference between the carole and the witches’ dance is that the witches face outwards. These are the dances described by Guazzo in his Compendium Maleficarum (1591), ‘which are performed in a circle but always round to the left.’ Guazzo explicitly diabolises the sabbat dance and exaggerates the disorder, describing how ‘each demon takes by the hand the disciple under his guardianship, and all the rites are performed with the utmost absurdity in a frenzied ring with hands joined and back to back; and so they dance, throwing their heads like frantic folk.’ The carole’s popularity waned by the beginning of the fifteenth century, as the basse danse rose in popularity, and as the stereotype of the witches’ sabbat began to emerge. The basse danse could be seen as a more solemn and dignified form, a processional dance characterised by low, gliding steps and no leaping.

Witches’ reel dance

The reel was another folk dance commonly performed in a circle, linked to the witches’ dance. The pamphlet, Newes from Scotland, published shortly after the North Berwick witch trials of 1590–92, reported the confession of Agnes Sampson, extracted after horrific torture, who testified to dancing a reel with ‘seven score’ witches ‘singing all with one voice.’ [20] ‘The Witches’ Reel’ is said to be the song that the North Berwick witches sang as they danced to raise a storm against King James, though I can find no source for the assertion. Only the first two lines – Cummer gae ye afore, cummer gae ye / Gin ye winna gae, cummer let me – come from the trial transcripts, the rest was artfully constructed by the folklorist F. Marian McNeill.

Other folk dances, such as the jig and the morris, were also perceived to have rebellious, subversive and demonic tendencies. Amanda Eubanks Winkler, in her study on the ways that theatrical music represented disorderly subjects, shows how dances were associated with and ‘performed’ witchcraft: ‘While round dances performed in a clockwise fashion mimicked the motion of the spheres and replicated divine harmony in bodily movement, witches’ rounds were often perversely performed counter-clockwise and back to back.’ [21]

Witches from the Salmacida spolia, 1640, the last masque performed at the English Court before the outbreak of the English Civil War.

She cites Ben Jonson’s Masque of Queenes (1609), which describes how the witches ‘fell into a magical dance full of preposterous change and gesticulation,’ and who ‘at their meetings do all things contrary to the custom of men, dancing back to back, and hip to hip, their hands joined and making their circles backward, to the left hand, with strange fantastic motions of their heads and bodies.’ She notes how the description, ‘encapsulated common ideas about witches’ terpsichorean practices, ideas that can be seen in nearly all seventeenth-century depictions of witches’ round dancing, theatrical and otherwise.’

The Masque of Queenes, with its ‘foil, or false masque’ of witches, is particularly noteworthy in flaunting Ben Jonson’s erudition and reading in continental demonology, as well as that of King James, for whom the ‘spectacle of strangenesse’ was composed. In annotations to the presentation copy of the manuscript, Jonson cites sixteen works of demonology to support his depiction of the witches, which has been described as the most complete presentation of the received opinions on witchcraft of the time. Of these works he drew directly from the following: Delrio’s Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex (Leuven, 1599), Rémy’s Dæmonolatreiæ libri tres (1595), Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia (Paris, 1531), Elich’s Dæmonomagia (Frankfurt, 1607), Spina’s Quaestio de strigibus (Rome, 1576), Bodin’s De la démonomanie des sorciers (Paris, 1580), Gödelmann’s Disputatio de magis, veneficis, maleficis et lamiis (1584) and James’ Dæmonologie (Edinburgh, 1597). Additionally, yet without citation on account of King James’ explicit disapproval of them, Jonson made use of Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), and Weyer’s De præstigiis dæmonum (Basel, 1563). [22] Whilst the eleven subordinate witches or ‘haggs’ are drawn from witchlore, their mistress has clear classical precedents, Canidia, Erichtho, Ate and Circe. The sixteen classical authorities referenced by Jonson include Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Seneca’s Medea, Lucan’s Pharsalia, Horace’s Epode 5 and Satire 1:8 and Apuleius’ The Golden Ass. Even these classical sources invoke earlier authorities, the witch is raised from an archaic mythic consciousness.

Jonson’s antimasque is meticulously constructed to flatter his patron, whose grasp of the political applications and implications of witchcraft was heavily informed by the continental demonology, particularly the thought of Bodin and Rémy, who asserted that the power of witchcraft waned if confronted by a higher authority. [23]

This belief was dramatically enacted in the North Berwick witch trials when Agnes Sampson, interrogated by James himself, had wondered why the witches’ sorcery was unable to harm the King, only to be enlightened by the Devil himself, ‘Il et un home de Dieu.’ Thus the witch and the devil legitimised the king and his divine right to rule. With the antimasque Jonson addresses James directly, holding up a mirror in which his majesty could contemplate his ideas. The theatrical schema, which ritualistically opposes twelve witches to the twelve ancient queens, is in accord with James’ own philosophising apocalyptic kingship. Stuart Clark comments, ‘demonism was, logically speaking, one of the presuppositions of the metaphysic of order on which James’ political ideas ultimately rested.’ [24] The triumph of the masque of queens over the witches’ masque is inevitable, as certain as the last judgement; and it consolidates power, political and religious, in the hands of James.

There is no mention of dancing witches in Dæmonologie, even so the dance is described by Jonson as ‘an usual ceremony at their convents or meetings,’ drawing from Rémy and Delrio in particular. The witches’ dance is the central motif in the spectacle of malefica, which synthesises elite discourse and reported confessions of demonised folklore, folk practice, fairytale, myth, epic and tragedy. The dance provides the occasion to do witchcraft.

Dancing bodies vividly enact the antithesis of divinely ordained sovereign power and the illicit and illusory power of witch and devil, of bodies that move in a self-controlled, graceful and harmonious manner and those who rudely twist and contort themselves with abandon. Writing on sorcery and sexuality in Baroque dance, VK Preston pointedly remarks, ‘Who dances, how one dances, and the perceived order (or disorder) of the dancing body could define, and moreover distinguish between, a legitimate and illegitimate subject in the world.’ [25]

Illustration from Durand’s Discours au vray (1617) showing a ballet depicting the sorceress Armide surrounded by a circle of ‘mocking spirits’ performed by men as vieilles or old women.

In France, the witch was an integral figure in the ballets de cour, where she was the king’s female double; his ‘exact and inverted image,’ according to the historian Robert Muchembled, ‘within a dualistic conception of things both political and religious.’ [26] Her role was to sow disorder so that the king could exercise his power and restore order. These spectacles, whether masque or ballet, whether performed on the public stage or at court, made explicit the association of female sexual license, exemplified by the whore or harlot, with the magical power of the sorceress. The restoration of sovereign authority, expressed choreographically by the movement from metamorphic, chaotic and disordered forms to geometric and harmonious ones, was thus a triumph of patriarchal order over a libidinous feminine chaos.

Jean Bodin, in his widely disseminated and influential De la démonomanie des sorciers, asserts that, ‘the violent witches’ dances make men mad, and make women abort,’ and as for the furor, ‘all raving and frenzied people perform such dances and violent leaps.’ [27] Bodin claimed that there was no more expedient method of curing them than to make them dance calmly, enforcing heavy rhythmic movements, as had been done with ‘the mad people in Germany struck with the illness known as St Vitus and St Modestus.’

Through Bodin’s allusion we can glimpse the dancing epidemics that broke out sporadically across central Europe, predominantly in France, Germany and Flanders in the Middle Ages. The phenomenon was variously known as chorea sancti viti, choreademonomania, the devil’s dance, or simply chorea. The earliest reference to such a dancing madness dates to 1021, when tradition records that 18 people gathered at a church in the German town of Kölbigk on Christmas Eve, ‘dancing and brawling in the churchyard.’

In one telling of the story, the local priest cursed the dancers for this blasphemy, to howl and carole unceasingly in their round. Four were said to have died of exhaustion, the others suffered for the rest of their lives from trembling in the limbs. Kélina Gotman draws attention to the power dynamics at play in the earliest outbreaks of dancing mania, noting that they, ‘suggested a battle of wills between recalcitrant celebrants and the doyens of the church. An “oft-repeated tradition” from the eleventh century suggests dancing was at the heart of battles for power.’ [28]

Dancers of St Vitus, Hendrik Hondius the Elder (1642)

In Decani Tongrensis, Radulphus de Rivo, a deacon from Tongeren, described the choreomaniacs as a devilish sect. ‘This is how it happened,’ he wrote, ‘persons of both sexes, possessed by devils and half-naked, set wreaths on their heads, and began their dances and that not only in the market places, but in churches and private houses. They were free of all modesty, and in their songs they uttered the names of devils never before heard of.’ The dancers were, in fact, Christian pilgrims, as Backman, citing Johannes de Beka’s chronicle, writes in his Religious Dances. They came, ‘from Bohemia, but also from Hungary, Poland, Carinthia, Austria, and Germany. Great hosts from the Netherlands and France joined them.’ [29]

The association of St John the Baptist with the dancing mania predates that of St Vitus. His feast, on 24th June, regarded as ‘the most ancient of the Christianised pagan dances,’ [30] was celebrated in earlier centuries with merry-making, dancing and flaming torches. Celebrants danced around or leapt over bonfires; an ancient tradition that was believed to assure fertility and a good harvest.

The dancers of St John were an ecstatic dancing sect which first appeared during the festival of the Baptist at Aachen in 1374. ‘They would dance through the streets, and in and out of churches until they were exhausted […] absorbed in their fantastic visions,’ writes Margaret Taylor.

Discussing this outbreak of wildly devotional dancing, Kathryn Dickason discerns the ambiguity inherent in these popular expressions of piety, ‘Since these dancers invoked St John the Baptist, some sources blamed Salome, the seductive saltatrix (female tumbler) for inflicting choreomania. Others report that choreomaniacs claimed to have beheld the head of St John swimming in blood while partaking in their own danse macabre.’ [31]

In The Black Death and the Dancing Mania (1808), Justus Hecker recounts how men and women, ‘formed circles hand in hand, and, appearing to have lost all control over their senses, continued to dance, regardless of the bystanders, for hours together in wild delirium, until at length they fell to the ground in a state of exhaustion.’ The compulsive, spasmodic movement at once possesses and exorcises, it is both pathology and therapy. Dickason remarks that, ‘even the earliest documentation depicts choreomaniacs as (literally) dancing between demon/deity, anguish/bliss, and decay/vigor.’ [32]

This ambiguity is inherent in the polysemic nature of dance, even within a Christian context. Dance is connected with celebration, worship and the holy, [33] but also with excess, unlicensed sexuality and the enormity of trance and possession. A comparable equivocacy can be observed in the figures and legends of the Baptist and the saltatrix. As patrons of excessive and proscribed dancing, they are caught in a net of associations encompassing female desire and sexuality, male authority and asceticism, menarchal rites of passage, menstruation, male sacrifice and martyrdom, headlessness and ecstasy. [34]

The head of John the Baptist in disco, Hans Gieng (1530/1560)

St John is one of the few saints to have two feast days: 24th June celebrates his birth and is associated with midsummer fertility festivals, 29th August remembers his passion or martyrdom. Besides his influence on choreomania, John was invoked against conditions in which movement was inhibited, erratic or extreme, such as acrophobia, cramps and epilepsy. John had denounced Herod for his marriage to the divorced wife of his exiled brother, a union that was considered incestuous in Judaic law; and medieval legend told how Herod Antipater and Herodias were struck with epilepsy in punishment for this transgression.

There is a tradition that John’s affinity with ecstatic dance goes back to the womb, as recounted in Luke 1:41, ‘When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greetings, the child leaped in her womb.’ In the Greek original the word translated as ‘leaped’ is eskirtesen, from skirtao, to leap for joy, to move in sympathy (as of the instinctive, primal movements of a foetus in utero). The Latin gives saltasset, from saltare, both to dance and to leap. The same word is used in the Latin of Mark 6:22, cumque introisset filia ipsius Herodiadis et saltasset, which translated the Greek kai eiselthouses tes thugatros autes tes erodiados kai orchesamenes – ‘and when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced.’

Strikingly, the word skirtao is also used in a Dionysian context, in The Bacchae of Euripedes, to describe the frolicking of goats. The leap, as Marcel Detienne notes, is the characteristic Dionysian movement. [35] Pedáo, a word in the same semantic field as skirtao, and its derivative ekpedao (to spring out, leap forth), give us ekpedan, a technical term for the Dionysiac trance. Whilst I do not identify the Baptist with Dionysos, as Jane Harrison did, I perceive in John’s association with ecstatic dance and prophecy, and in the wild, roving enthousiasmós of his devotees, a reemergence and transformation of the emotional mysticism of archaic pagan cults.

The unnamed daughter of Herodias is Salome [36], herself the inciter of a dance craze, the fin de siècle Salomania [37], and the archetype of the femme fatale. But that comes much later, and is a vision of late 19th century decadence. To medieval and early modern audiences, as attested by her iconography, she is a girl on the threshold of womanhood [38], the kybisteter who sets in motion the most aeonic of revolutions with her twisting, tumbling, leaping body. Kybistan denotes acrobatic actions in general, and specifically the somersault, the action of turning back on oneself, with the head and feet touching in its most extreme expression. The posture is familiar to us as Charcot’s arc-de-cercle, or arch of hysteria. Kybistan is derived from Greek kýbe, an obscure word for head; a curious resonance with the martyrdom of John, as Salome turns on her head, the Baptist loses his.

From late antiquity, the legend of Salome was held up as the principal negative exemplum of dance. Origen (died 253 ce) commented, ‘the dance of the daughter of Herodias was opposed to the holy dance.’ [39] Gregory of Nazianzus (died 390 ce), despairing of a ‘dancer’s charms’ describes, ‘the diverse contortions and sexually ambiguous postures’ of the dancer’s body; the use of the word katorcheisthai – from katorchéomai, to dance in triumph over, or to subdue or enchant by dancing, literally to dance down or against – elicits an atmosphere of conflict, subjection and sorcery. For some, the very existence of a holy dance was unthinkable. With his terse denunciation, ‘where there is dance, there is the devil,’ John Chrysostom (died 407 ce) censured all delights (and dangers) of bodily jouissance in the formative Christian Church. His influence, along with the other Church Fathers, extended to the early modern and beyond, and should be considered as crucial to the demonologists’ voyeuristic speculations on the witches’ dance and the conspiratorial sabbat. The notion of a dance in hell, in opposition to the heavenly dance, was introduced by the post-Nicene Church Fathers, who imagined an orchesis diabolou [40], a dance of the devil, in dualistic conflict with Christ, both mirroring and justifying their own ideological war with heretics. James Miller, in his monumental Measures of Wisdom, draws attention to the rhetorical comparison of the two antithetical dances in early Christian sermons; a juxtaposition that was similarly strategically employed in the masque and the ballet de cour.

In De spectaculis, Tertullian (died 240 ce) portrayed theatre as the unholy communion of the ‘demons of drunkenness and lust,’ [41] Bacchus and Venus. Theatrical performances were regarded by the early Church as intrinsically pagan. Dance, in particular, was linked to idolatry, with reference to the biblical narratives of the golden calf and the priests of Baal in Exodus 32:19 and 1 Kings 18:26. Moreover, dance was deemed the chief mode of movement of the demonic, the dancer’s ever shifting mutability equated with the inconstant motion of demons.

Early Christian homiletic, like early modern witchcraft literature, is charged with anxiety about women, their bodies, and their dancing. With a sharp tongue Chrysostom inveighs against Herod’s banquet, ‘O diabolical revel! O satanic spectacle! O lawless dancing!’ Behind such damning attacks I detect an implicit recognition that the dancer possesses a persuasiveness exceeding male rhetoric and discourse. The male eye was vulnerable to the beguiling bodily language of women, and through its gaze his soul was put to death. Chrysostom, and the other Fathers, discerned in dance a similitude of the logos of male discourse, as evinced by the language used to describe Salome’s dancing; the word schemata, for instance, being both a figure of speech, and the gesture or appearance. But if the Church Fathers drew attention to the similarity of the rhetorics of logos and body, it was ultimately to heighten the sense of alterity, the sheer otherness of women’s bodies. Feminine dance was an embodied discourse, at once morally inferior, and destructive to, the intellect animating male discourse. Dance is an art of flesh, so remarkable in its sensuous malleability; and of mimesis, the primary modus operandi of the devil in the world. It is, moreover, a tradition transmitted within the haram spaces of women.

In ‘Salome’s Sisters: The Rhetoric and Realities of Dance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium,’ Ruth Webb translates the arresting description of Salome’s dance by Basil of Seleucia (died 468 ce) in his sermon In Herodiadem: ‘She was a true image of her mother’s wantonness with her shameless glance, her twisting body, pouring out her emotions, raising her hands in the air, lifting up her feet as she celebrated her own unseemliness with her semi-naked gestures.’ [42]

The Church Fathers placed great emphasis on the relationship between Herodias and Salome, as Webb observes, ‘Salome’s dance is an art learned from Herodias.’ In antiquity, as in the medieval and early modern periods, education was restricted and literacy amongst women was uncommon. Dance, and bodily practice generally, is perhaps indicative of a female education and culture of transmission, that may, as Webb conjectures, ‘take us closer to some elusive forms of female experience.’ Webb concludes that, ‘whilst we cannot prove the existence of the tradition of female dance to which Basil, Theodor and Ambrose seem to refer in their depictions of Herodias and her daughter, neither can we deny the possibility of its existence.’ A phenomenological account of the mother-daughter relationship may illuminate these elusive forms of female experience. Maxine Sheets-Johnstone astutely describes movement as ‘our mother tongue.’ [43] It is the kinetic and tactile language out of which the logos is wrought. The transmission of the erotic from mother to daughter is given through touch, through the kinaesthetic, affective and emotional intimacy of the relationship. I find this understanding more compelling, for being enfleshed, than the analysis of the Herodias-Salome dynamic by René Girard, whose notions of ‘mimetic desire’ and ‘mimetic violence’ are elegant, and intellectually stimulating, but lacking the true insight of an embodied reading.

Whether the medieval dancers were inspired or cursed, and whether by Salome or St John, is moot. The dancing manias erupted in the wake of the black death. The plague was blamed for setting in motion a contagion of disordered movements across vast swathes of medieval Europe. [44] Some claimed that the plague was caused by dancing, others believed that it had entered Europe with the gypsies. But from medieval accounts of the dancing manias, it is clear that, far from being a mass delusion, ergot poisoning or epidemic, the convulsive outbreaks of dancing across Europe were brought by pilgrimages of unorthodox or heretical religious sects. The pilgrimages were part of a complex, fluid economy incorporating all classes of society, and involving diplomatic, legal, ecclesiastical, commercial, migratory, therapeutic, devotional and criminal praxes. As the Arabic saying goes, fi’l-haraka baraka, there is blessing in movement; a sentiment not entirely shared by the ruling class in early modern Europe. At this stage the modern nation state had not yet been established. Extensive territories lay outside the authorities’ control, boundaries were less fixed, and the assimilation of people to the state had not been accomplished. In this period the nation state was being theorised by political theologians such as Bodin, and its existence made a matter of urgency by the appeal to a conspiracy of (dancing) witches. ‘But it is well to note that there is no assembly where they do not dance,’ wrote Bodin [45], ‘and, according to the confession of the witches of Longny, while dancing they chant har, har, Devil, Devil, dance here, dance there, play here, play there: and the others sing Sabbath! Sabbath!, namely the feast and day of rest, while raising their hands and besoms aloft to testify and give a certain testimony of exultation, and that they willingly serve, and adore the Devil, and to counterfeit the adoration which is due to God.’

In the holy war against witches, dance came to be the most damning evidence of guilt. For Guazzo, it was the ‘weightiest proof’ of witchcraft since it left circular traces in the grass where the witches had trod. In the demonologists’ tracts we read the choreography of power. Bodin’s theories on sovereignty and witchcraft cannot be separated, De la démonomanie des sorciers must be considered alongside Les six livres de la république (1576). The king rules the state by means of the state of exception, that is, the suspension of the existing order, placing him as sovereign power against the chaotic conspiracy of bodies.

The convergence of social, religious and political interests with the dancing body reaches a climax with la volta, a dance which enjoyed a wild popularity, and scandalous reputation, throughout Europe. Bodin condemns it, revealing that it was, ‘brought by witches from Italy to France,’ a claim repeated by Scot in his Discoverie of Witchcraft. But whereas Scot intended to refute the superstitions of ‘lewd inquisitors and peevish witchmongers,’ Bodin aimed to mobilise such beliefs for theological and political ends. The volta, he continues, ‘beyond the insolent and impudent movements, is cursed to bring about an infinity of murders and abortions, which is a matter of highest consequence for the republic, and must be prohibited most rigourously.’ In his concern with the protection and increase of life, and its proper ordering, through the desired prohibition of certain forms of dance and physical expression, we can observe an early form of biopolitics.

Engraving of a witches’ sabbat by Jan Ziarnko, from Pierre de Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et demons. Paris (1613)

If Bodin’s sovereign and state come into focus through the measured control of excessive movement, de Lancre finds himself, the sole agent of God’s constancy, in the Pays de Labourd, a land he perceived to be in constant and turbulent motion. De Lancre turns his attention, in Book 3, discourse IV of Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et demons (1612), to the witches’ dances, which can be understood as a study ‘of inconstancy in its most extreme form.’ [46] Referring to la volta, he disputes Bodin and asserts a Provençal origin for this ‘ecstatic dance performed by people out of their senses.’ Examining conceptions of space and travel in de Lancre’s writings, Thibaut Maus de Rolley draws out the ‘demonization of movement’ in the demonologist’s ouevre, situating witchcraft within a wild, agitating landscape and a culture of seafaring, covert sabbats, frenzied dancing, travelling demons, and flight. In this space, woman was ‘the most excellent Hieroglyph of inconstancy that one could lay eyes upon,’ [47] and dancing, which de Lancre treats in greater detail than any other demonologist, appears as the supreme temptation and expression of the devil’s corrupting influence.

Not all ecclesiastics were against dance; the Jesuits, for instance, regarded it as beneficial for the health and wellbeing of people. The cleric Jehan Tabourot, guising himself (anagrammatically) as the dancing master Thoinot Arbeau, described the volta in his Orchésographie (1589), and instructs how to perform the dance correctly, ‘he who dances the lavolta must regard himself as the centre of a circle and draw the damsel as near to him as possible […] When you wish to turn release the damsel’s left hand and throw your left arm around her, grasping and holding her firmly by the waist above the right hip with the left hand. At the same moment place your right hand below her busk to help her to leap when you push her forward with your left thigh.’ The volatility of the spinning and leaping characteristic of la volta oblige a degree of physical intimacy, and strength. This, together with the excitement, dizziness and breathlessness it caused the dancers, must account for both its popularity and its infamy. The lifting shamelessly revealed the underskirts or naked thigh of the woman, such that la volta was an unambiguous allusion to sex in the literature of the period.

Fascinatingly, in Elizabeth I, the exact and inverted images of sovereign and witch converge in the dance. The queen was renowned, and decried, for the virtuosity of her dancing, and la volta was said to be her favourite. In her political and diplomatic strategies, as prince and woman, Elizabeth conjoined verbal and bodily rhetorics in a calculated display of power [48] – the power of the state embodied through the power of the witch. I propose that we, like Elizabeth, exercise our power and develop our full potential for communication, through language and movement alike.

Dancing unifies and binds, bringing a multiplicity of perspectives into relation. Through the circling of dancers, the kinetic and psychic territories of witchcraft and state interpenetrate. The demonological imagination commingles with the realm of folk belief and practice; courtiers and peasants, priests and layfolk, those who condemn and those who delight, all are moved.

Kinaesthetic imaginaries

My first experience of the sabbat and its dance was in dream, when I was taken on Walpurgis Night. The taking felt as it always does when I am transported by another’s volition, with the sensation of being drawn at great speed through a vortex of light and sound. But where I found myself bears only slight comparison to previous oneiric adventures. I am not I, immerged in an awareness that permeates the space: a phantasmagoria of forms, bodies, limbs revolving, whirling … nothing is distinct or separate, all is in flux, interpentrating and rending incessantly. The feeling is intensely, viscerally sexual, but in no way human; it is pure sensation, without culture or condition. Consciousness is torn from the remnants of bodies, as shapes conjoin, are pulled apart, disintegrate. The kinaesthetic sensation is overwhelming, almost unbearable, neither precisely pain nor pleasure, but something of both, an ecstatic annihilatory turmoil. By contrast, the visual aspect of the dream was muted and obscure; the only light a murky and dull glow emanating from the bodies, pervading the dream space.

Dance dreamt or imagined arises from the dance in flesh, they merge into one another. The kinaesthetic imaginary of the witches’ dance – that is, the felt experience of the dancers, their inner space of muscle, sinew, emotion, fantasy and dream pulsing with blood – is absent from the demonological texts. It is born from the clandestine subjectivity of each dancer, and emerges into the realm of intersubjective experience within the circle of others.

The kinaesethetic sense is the sense of movement; it is the originary sense, coeval with life, and synaesthetically binds all the others. To move is to feel, to have knowledge: of self, and one’s interior landscape; and of others, and the manifold worlds we inhabit.

This knowledge is power. To whirl, to leap, to fly, to crouch, to spring; to know this within the body is power. To sing, to howl, to cast off the skin, to cast the eye is power. I know this power. I know how it feels to shift, to sense the pelt bristle from my skin, to feel the presence electrify my spine, the atavism torn from its slumber. I know how to open my wound and cross the river of blood. I know how to open my eyes in dream, how to see and be seen, and not be seen; how to take on other bodies, how to take flight. In dream the kinaesthetic is an underrealm in which we vividly and palpably encounter our flesh in its strange, archaic and potential forms; and in which we interact with other agencies – human and nonhuman beings, living and dead alike. Indeed, it has been observed that kinaesthetic sensations are a central feature of lucid dreaming. [49] The sense of agency, of knowing- how, and hence power, derive from the primal sense of movement; a reflexive awareness that inheres throughout consciousness.

Hence, I trace a phenomenological continuum from the weakly embodied states [50] of the dreaming or psychedelic self (or selves) to those immersive states of deep embodiment which I seek in possession and performance. Movement is intrinsic to this experiential continuity grounded in the phenomenology of the living body. Dance, the conscious elaboration of this energy, patterns, holds and integrates the knowledge and power elicited from the diverse states of embodied consciousness. This understanding is fundamental to the way I practice and experience magic. I have oriented my work towards an enquiry into the body and its mysteries, the occulted body. Its knowing is primarily that of the dark senses – kinaesthesia, proprioception and touch. Its method – a feeling into [51] the other – is an affective and intuitive search for the unknown, for mystery.

In my weyward circumvolution of the witches’ dance, I was impelled by the need to situate my own practice and experiences within the counter traditions and histories of dance and of theology. As a construct of Christian demonological imaginaries encountering the feared others, the witches’ dance is a dynamic and complex motif to interrogate, to feel into.

I too have encountered others in this dance, have glimpsed and felt them in my body.

This work was first presented in Seattle at the Texts and Traditions Colloquium on the 15th September 2018, and is published in The Brazen Vessel (Scarlet Imprint 2019).

NOTES

1) 1914, 1926, and 1934. Kolb, Alexandra, 2016.

2) Isaiah 13:21, ‘But wild beasts of the desert shall lie there; and their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there.’

3) Bailey, Michael D., 2013.

4) The Franciscan preacher ‘stands at such a crucial moment in the elite construction of diabolical, conspiratorial stereotypes of witchcraft.’

5) Wescoat, Bonna D., 2012.

6) Blécourt, Willem de, 2013.

7) Nevile, Jennifer, 2008.

8) Langer, Susanne K., 1953.

9) Hutton, R. E., 2014.

10) Pavanello, M., 2016: 63 (note 90).

11) Burton, Robert, 1621. Anatomy of Melancholy. ‘Terrestrial devils, are those Genii, Faunes, Satyres, Wood-Nymphs, Foliots, Fairies, Robin Goodfellows … which are as they are most conversant with men, so they do them most harm … some put our fairies into their ranke (with Dagon, Beli, Astarte, Balls and other earth Gods), which have in former times been adored …’

12) Latham, Minor White, 1930: 91.

14) Henderson and Cowan, 2001.

14) Guðmundsdóttir, Aðalheiður, 2005.

15) The others being the line dance and the couples dance.

16) Chemero, A., 2016.

17) Garfinkel, Y., 2010.

18) Sachs, Curt, 1963.

19) Mullally, Robert, 2011.

20) Hirsch, Brett D., 2013.

21) Eubanks Winkler, A. ,2007.

23) Furniss, W. Todd, 1954: 344–60.

23) Clark, Stuart, 1977.

24) Clark, Stuart, 1977.

25) Preston, VK, 2015: 62

26) Muchembled, Robert, 1993.

27) ‘Mais les danses des Sorciers violentes rendent les hommes furieux, & font auorter les femmes: comme on peult dire que la volte, que les Sorciers ont amené d’Italie en France, outre les mouvements inſolens, & impudiques, à cela de malheur, que une infinité d’homicides & auortemens en adviennent Qui est chose des plus considerables en la republique, & qu’on demeure defendre le plus rigoureusement. Quand à la fureur, on voit evidemment, que tous les hommes furieux, & forcenez usent de telles danses, & sautz violens: Et n’y a moyen plus expedient pour les guarir, que de les faire danser posément, & en cadence pesante, comme en faict en Allemaigne aux insensez qui sont frappez de la maladie qu’on dict de S. Vitus, & Modestus.’

28) Gotman, Kélina, 2018: 61.

29) Backman, 1952: 331

30) Taylor, Margaret, 1990.

31) Dickason, Kathryn, 2012.

32) Dickason, Kathryn, 2012.

33) Benveniste E. ‘The Sacred’ in Indo-European Language and Society. London, 1973: 460. The Greek hierós signifies what is godlike, having the qualities of holiness and movement, vitality, swiftness and circularity.

34) These themes informed my dance The decollation of flowers, which I performed in Benevento on St John’s day. My choreography revisions the dance of Salomé as the bloody flowering of the erotic body and sexuality in relation to male, female and divine others.

35) Detienne, Marcel. Dionysos à ciel ouvert. Hachette, 1986.

36) The source for her name comes from Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.136

37) ‘Salomania’ is Nancy Pressly’s term for the profusion of Salomes in the arts at the end of the 19th century. See her Salome: La belle dame sans merci. San Antonio: San Antonio Museum of Art, 1983. Exhibition catalogue: 1 May–26 June 1893.

38) In Greek, korásion, a diminutive of kore. The descriptor reveals her to be still a child, that is, premenarchal, thus not yet marriageable. The word also denoted the pupil or ‘apple’ of the eye. The English word is derived from Latin pupilla, the diminutive form of pupa (girl, doll, puppet; and the tiny image of oneself seen reflected in another’s eye).

39) In Matthaeum X:22

40) Miller, James. 1986.

41) ‘But Venus and Bacchus are close allies. These two evil spirits are in sworn confederacy with each other, as the patrons of drunkenness and lust.’ De spectaculis X. Pagan deities and daemons are frequently glossed as demons or evil spirits, to avoid naming them.

42) Webb, 1997.

43) Sheets-Johnstone, M. The Primacy of Movement. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins University Press, 2011: xxv.

44)Compare also the iconography of the dance of death (danse macabre, totentanz or danza de la muerte).

45) ‘Mais il faict bien à noter que il ne se faict point de l’assemblée où l’on ne danse, & par la confession des sorcières de Longny elles disoyent en danſant, har, har, Diable, Diable, faute icy, faute là, ioüe icy, ioüe là: Et les autres disoient, Sabath! Sabath! c’est à dire, la feste et iour de repos en haussent les mains & balets en hault pour testifier & donner un certaine temoignage d’allegresse, & que de bon cueur ils seruent, & adorent le Diable, & aussi pour contrefaire l’adoration qui est deuë à Dieu.’ Jean Bodin, De la démonomanie des sorciers, Livre 2, chapitre 4: 88.

46) Maus de Rolley, Thibaut, 2017: 2.

47) ‘le plus excellent Hieroglyphe d’inconstance qui se peut voir.’ Lancre, Tableau de l’inconstance et instabilité de toutes choses, fol. 67r (cited in Maus de Rolley, T., 2017)

48) Mirabella, Bella. 2012.

49) Nielsen, T. A. ‘Kinesthetic imagery as a quality of lucid awareness: Descriptive and experimental case studies.’ 1986.

50) I am drawing particularly on the research of Jennifer M. Windt, who proposes that ‘dreams are weakly phenomenally and functionally embodied states, in which bodily experience is attenuated as compared to standard wakefulness but still remains connected in interesting and systematic ways to the sleeping body.’

51) ‘Feeling into’ in reference to the concept of Einfühlung, first articulated by the philosopher Robert Vischer, and translated into English as empathy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arbeau, Thoinot. Orchesography, translated by Mary Stewart Evans with new notes by Julia Sutton and Mireille Backer, New York: Dover, 1967.

Arcangeli, Alessandro. ‘Dance and Punishment.’ Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 10, no. 2 (1992): 30–42.

—. ‘The savage, the peasant and the witch.’ European Drama and Performance Studies, n° 8, 2017–1, Danse et morale, une approche généalogique: 71–91.

Backman, E. L. Religious dances in the Christian church and in popular medicine. London, 1952.

Bailey, Michael D. ‘Nocturnal Journeys and Ritual Dances in Bernardino of Siena.’ Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 8, no. 1 (2013): 4–17

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. The Dancing Goddesses: Folklore, Archaeology, and the Origins of European Dance. New York: W.W. Norton, 2013.

Bartholomew, Robert. E. ‘Rethinking the Dancing Mania.’ Skeptical Inquirer 24 (July/August 2000): 42–47.

— . ‘Tarantism, Dancing Mania, and Demonopathy: The Anthro-Political Aspects of “Mass Psychogenic Illness.”’ Psychological Medicine 24:2 (May 1994): 281–306.

Blécourt, Willem de. ‘Sabbath Stories: Towards a New History of Witches’ Assemblies’ in: Brian P. Levack (ed.), Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013: 84–100

Chemero, A. ‘Sensorimotor Empathy.’ Journal of Consciousness Studies, 23, 5–6 (2016): 138–152.

Clark, Stuart. ‘King James’s Daemonologie: Witchcraft and Kingship.’ The Damned Art: Essays in the Literature of Witchcraft. Edited by Sydney Anglo. London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

— . 1997. Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modem Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dickason, Kathryn. ‘Stepping into a Spiritual Economy: Medieval Choreomania and the Circulation of Urban Sanctity.’ Society of Dance History Scholars 2012 Proceedings, Society of Dance History Scholars (2012): 95–108.

Winkler, Amanda Eubanks. O Let Us Howle Some Heavy Note: Music for Witches, the Melancholic, and the Mad on the Seventeenth-Century English Stage. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Frecska, Ede, and Zsuzsanna Kulcsar. ‘Social Bonding in the Modulation of the Physiology of Ritual Trance.’ Ethos 17, no. 1 (1989): 70–87.

Furniss, W. Todd. ‘The Annotation of Ben Jonson’s Masqve of Qveenes.’ The Review of English Studies 5, no. 20 (1954): 344–60.

Garfinkel, Y. Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture. Austin: University of Texas Press. 2003.

— . ‘Dance in Prehistoric Europe.’ Documenta Praehistorica, 37 (2010): 205–214.

Girard, René. ‘Scandal and the Dance: Salome in the Gospel of Mark.’ New Literary History 15, no. 2 (1984): 311–24.

Gotman, Kélina. Choreomania: Dance and Disorder. Oxford Studies in Dance Theory, Oxford University Press, 2018.

Guðmundsdóttir, Aðalheiður. 2005. ‘“Nú er glatt í hverjum hól’”: On How Icelandic Legends Reflect the Prohibition of Dance.’ The 5th Celtic-Nordic-Baltic Folklore Symposium on Folk Legends, June 15th–18th 2005, Reykjavík.

Henderson and Cowan. Scottish Fairy Belief. East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2001.

Hirsch, Brett D. ‘Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux?’ Early Theatre 16, no. 1 (2013): 139–49.

Hutton, R. E. ‘The Wild Hunt & the Witches’ Sabbath.’ Folklore, 125(2), 2014: 161–178.

Kolb, Alexandra. ‘Wigman’s witches: Reformism, Orientalism, Nazism’ Dance Research Journal, 48 (2) 2016: 26–43.

Langer, Susanne K. Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art Developed from Philosophy in a New Key. New York: Charles Schribner’s Sons, 1953.

Latham, Minor White. The Elizabethan Fairies: The Fairies of Folklore and the Fairies of Shakespeare. NY: Columbia University Press, 1930.

Maus de Rolley, Thibaut. ‘Of Oysters, witches, birds, and anchors: Conceptions of space and travel in Pierre de Lancre.’ Renaissance Studies, 2017.

Miller, James. Measures of Wisdom: The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press, 1986.

Mirabella, Bella. ‘“In the sight of all”: Queen Elizabeth and the Dance of Diplomacy.’ Early Theatre 15, no. 1 (2012): 65–68.

Muchembled, Robert. Le roi et la sorcière: L’Europe des bûchers XVe-XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Desclée, 1993.

Mullally, Robert. The Carole: A Study of a Medieval Dance. Ashgate, 2011.

Nevile, Jennifer. Dance, Spectacle, and the Body Politick, 1250–1750. Indiana University Press, 2008.

Pavanello, M. (Ed.). Perspectives on African Witchcraft. New York, London: Routledge, 2016.

Preston, VK. ‘“How do I touch this text?”: Or, The Interdisciplines between: Dance and Theatre in Early Modern Archives’ in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater. Edited by Nadine George-Graves. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Rémy, Nicolas. Demonolatry. Trans. by E. A. Ashwin, ed. by Montague Summers. . London: J. Rodker, 1930 (first published 1595).

Roper, Lyndal. Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

— . The Witch in the Western Imagination. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Sachs, Curt. World History of the Dance. Translated by Schönberg, Bessie. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1963.

Schnusenberg, Christine C. The Mythological Traditions of Liturgical Drama: The Eucharist as Theater. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2010.

Soar, K. ‘Circular Dance Performances in the Prehistoric Aegean’ in: A. Chaniotes, S. Leopold, H. Schulze, E. Venbrux, T. Quartier, H. Wojtkowiak, J. Weinhold and G. Samuel, eds. Ritual Dynamics and the Science of Ritual II: Body, Performance, Agency and Experience. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 2010: 137–156.

Taylor, Margaret. ‘A History of Symbolic Movement in Worship.’ Dance as Religious Studies. Edited by Adams, Douglas & Diane Apostolos-Cappadona. N.Y.: Crossroad Pub. Co., 1990.

Tsitsou, Lito, and Lucy Weir. ‘Re-Reading Mary Wigman’s Hexentanz II (1926): the Influence of the Non-Western “Other” on Movement Practice in Early Modern “German” Dance.’ The Scottish Journal of Performance 1, no. 1 (2013): 53–74.

Webb, Ruth. ‘Salome’s Sisters: The Rhetoric and Realities of Dance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium.’ in L. James (ed.) Women, Men and Eunuchs: Gender in Byzantium. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

— . ‘Where there is dance there is the Devil: Ancient and modern representations of Salome.’ F. Macintosh (ed.) The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: 123–144.

Wescoat, Bonna D. ‘Coming and Going in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace.’ In: Bonna D. Wescoat and Robert G. Ousterhout (eds.). Architecture of the Sacred: Space, Ritual, and Experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Williams, Gordon. A Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart Literature. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press, 1994.

Williams, Seth Stewart. ‘[They Dance]: Collaborative Authorship and Dance in Macbeth.’ The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Dance. Lynsey McCulloch and Brandon Shaw (eds.). New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Windt, Jennifer M. Dreaming: A Conceptual Framework for Philosophy of Mind and Empirical Research. MIT Press, 2015.

Zika, Charles. The Appearance of Witchcraft: Print and Visual Culture in Sixteenth-Century Europe. London and New York: Routledge, 2007.